World War II: The War That Changed Everything

How a European border dispute escalated into the most destructive conflict in human history

The Global Conflagration: How Six Years of Total War Reshaped Human Civilization

On September 1, 1939, German forces crossed the Polish border and Europe plunged into what would become the most catastrophic war in human history. What began as a seemingly conventional European territorial dispute would escalate into a global conflagration involving every inhabited continent and fundamentally altering the course of human civilization.

By the time Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945, an estimated 70-85 million people had died—more than the entire population of Germany at the war's start. The world that emerged from this six-year nightmare was unrecognisable from the one that had entered it.

Yet World War 2 was more than unprecedented destruction. This was the conflict that ended European colonial dominance, established the United States and Soviet Union as superpowers, accelerated technological development by decades, and created the international institutions that still govern global politics today. The United Nations, NATO, the European Union, the State of Israel, Communist China, and the nuclear age all emerged directly from this war's aftermath.

The Prelude: How Peace Failed

The Second World War emerged from the unresolved tensions of World War 1. The Treaty of Versailles imposed harsh terms on Germany while failing to create sustainable security. The Great Depression shattered faith in democratic capitalism, particularly benefiting fascist movements that blamed democratic weakness for national suffering.

The League of Nations proved helpless when faced with determined aggression. Japan's invasion of Manchuria (1931), Italy's conquest of Ethiopia (1935), and Germany's remilitarization of the Rhineland (1936) all violated international law but faced no effective response. This pattern of appeasement taught aggressive powers that international law could be violated with impunity.

Blitzkrieg: The Revolution in Warfare

Germany's early victories demonstrated a revolutionary approach that combined tanks, aircraft, and radio communications to achieve unprecedented speed in military operations. Blitzkrieg—"lightning war"—emphasised movement, surprise, and psychological shock rather than World War 1's static trench warfare.

The invasion of Poland showcased these tactics devastatingly. German armies, supported by air power, defeated Poland within a month. The German offensive in Western Europe beginning May 10, 1940, achieved even more spectacular success. France, considered Europe's strongest military power, surrendered after just six weeks of fighting.

Description: Germany invading Poland, September 1, 1939

Publisher: Encyclopædia Britannica

Image Source: https://www.britannica.com/event/World-War-II#/media/1/648813/74903

Britain Stands Alone: The Battle for Survival

With France defeated and the Soviet Union bound by non-aggression with Germany, Britain faced the Nazi war machine alone. Yet Britain's survival had been made possible by one of history's most remarkable evacuations. Between May 26 and June 4, 1940, over 338,000 British and French troops were rescued from the beaches of Dunkirk by an improvised fleet of naval vessels, fishing boats, pleasure craft, and ferries. While the evacuation was a military defeat—the British Expeditionary Force had been driven from continental Europe—it preserved the trained personnel necessary for Britain's continued resistance and became a symbol of British resilience.

Churchill's Finest Hour As France fell and Britain stood isolated, Winston Churchill faced his greatest political crisis. Within his own War Cabinet, Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax and former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain advocated exploring peace negotiations with Hitler through Italian mediation. They argued that Britain's position was hopeless and that negotiating while still holding some cards was preferable to inevitable defeat and harsher terms later.

Churchill rejected this approach absolutely, understanding that any negotiation with Hitler would lead to British subjugation. In crucial War Cabinet meetings between May 26-28, 1940, Churchill argued that Britain could continue fighting from the Empire even if the home islands fell. His decisive moment came when he addressed the full Cabinet of 25 ministers, declaring they would fight on "however long and hard the road may be." The Cabinet's unanimous support ended serious consideration of surrender, ensuring Britain would fight on regardless of the odds.

"We Shall Fight on the Beaches" On June 4, 1940, as the last ships returned from Dunkirk, Churchill addressed the House of Commons in what would become one of history's most famous speeches. Speaking to a nation that had just witnessed the fall of France and the near-destruction of its army, Churchill needed to prepare Britain for invasion while maintaining morale. His speech acknowledged the military reality—Dunkirk was a "colossal military disaster"—but transformed it into a declaration of unwavering resistance. Churchill's soaring rhetoric culminated in his famous promise that Britain would defend every inch of territory and never surrender, even if the government had to continue the fight from the Empire. The speech galvanised parliamentary support and, when broadcast, steeled British resolve for the trials ahead.

"We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender”

Hitler's plan to invade Britain required first achieving air superiority. The resulting Battle of Britain (July-October 1940) became the first major campaign fought entirely by air forces. British advantages in radar technology, pilot training, and aircraft production gradually overcame German numerical superiority. The Luftwaffe's failure to destroy the Royal Air Force made invasion impossible and marked Hitler's first major strategic defeat.

The frustrated German strategy shifted to bombing British cities—the London Blitz—which killed over 40,000 civilians but failed to break British morale, demonstrating that air attacks alone couldn't defeat determined populations with strong institutions.

Breaking the Unbreakable Code While bombs fell on London, a secret war was being fought at Bletchley Park, where British codebreakers led by mathematician Alan Turing were working to crack the German Enigma machine. The Enigma cipher was considered unbreakable—generating trillions of possible combinations that changed daily. Turing's revolutionary approach involved building electro-mechanical devices called "Bombes" that could test thousands of possible settings in hours rather than years.

The breakthrough came from recognizing patterns in German communications and exploiting human error in Enigma operation. By 1942, British intelligence was regularly reading high-level German military communications, intelligence codenamed "Ultra." This provided crucial advantages in the Battle of the Atlantic, where knowing U-boat positions saved countless merchant vessels, and later campaigns where Allied commanders could anticipate German movements. Historians estimate that breaking Enigma shortened the war by two years and saved millions of lives—a victory won not on battlefields but in the quiet halls of academic brilliance.

Barbarossa: The Clash of Titans

Hitler's invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, opened the largest and most destructive theatre. Operation Barbarossa involved over 3.8 million Axis troops advancing along a 1,800-mile front. German forces initially achieved spectacular success, capturing Kiev, besieging Leningrad, and advancing to within sight of Moscow.

The German advance stalled during the brutal Russian winter of 1941-42. German forces, equipped for a short campaign, faced temperatures dropping to -40°F while Soviet counteroffensives pushed them back from Moscow. This marked a crucial turning point—German forces had failed to achieve quick victory.

The Eastern Front became a "war of extermination" with systematic murder of Soviet prisoners, civilians, and Jewish populations. This deliberate brutality stiffened Soviet resistance and ensured unprecedented savagery on both sides.

Pearl Harbor: America Enters the War

Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, transformed a European conflict into a truly global war. Japanese expansion in China had created escalating tensions with the United States. American economic sanctions forced Japanese leaders to choose between abandoning Chinese conquests or attacking American positions.

The Pearl Harbor attack achieved tactical surprise but strategic failure. While damaging the U.S. Pacific Fleet, it unified American public opinion behind total war. American entry transformed the strategic balance—the United States possessed the world's largest industrial economy and would eventually outproduce the combined Axis powers by enormous margins.

The Holocaust: Industrial Genocide

The systematic murder of European Jewry represented an unprecedented crime that revealed the ultimate logic of Nazi racial ideology. Nazi persecution evolved from legal discrimination through violence to systematic extermination—the "Final Solution" formalized in early 1942.

The death camps applied modern industrial techniques to mass murder. Facilities like Auschwitz-Birkenau could kill thousands daily using methods designed for maximum efficiency. This industrialization created killing on a scale exceeding anything in previous human history, requiring active participation and passive acquiescence from millions of ordinary people.

The Turning Tide: 1942-1943

The Battle of Stalingrad (August 1942-February 1943) became the war's most important engagement. German forces became trapped in urban warfare while Soviet forces encircled the entire German 6th Army. This destruction marked the beginning of continuous German retreat and demonstrated that German forces could be decisively defeated.

The Battle of Midway (June 4-7, 1942) destroyed much of Japan's elite naval aviation and ended Japanese expansion in the Pacific. American code-breaking enabled a defensive victory that shifted Pacific momentum decisively.

British victory at El Alamein (October-November 1942) ended Axis threats to the Suez Canal and began North African liberation, demonstrating Allied coordination and providing crucial amphibious operation experience.

D-Day: The Liberation of Europe

The Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, represented the largest amphibious operation in military history. Despite poor weather and fierce resistance, Allied forces successfully established beachheads, demonstrating Allied advantages in industrial production, technology, and coordination that Germany could no longer match.

D-Day ensured Germany would face overwhelming pressure from both east and west. Allied forces advanced rapidly across France while Soviet forces launched massive eastern offensives. By early 1945, the collapse of German resistance accelerated as the war economy crumbled.

Description: American assault troops in a landing craft during the Normandy Invasion, June 6, 1944

Publisher: Encyclopædia Britannica

Image Source: https://www.britannica.com/event/Normandy-Invasion#/media/1/418382/97251

The Pacific War: Island Hopping to Victory

The Pacific Theatre required different strategies emphasising naval power and amphibious operations across vast distances. Rather than attacking every Japanese position, American forces captured key islands while bypassing heavily fortified positions, conserving resources while advancing toward Japan.

The final campaigns at Iwo Jima and Okinawa revealed the costs of invading Japan itself. Despite overwhelming American advantages, Japanese resistance inflicted heavy casualties, influencing American decisions about using atomic weapons rather than conventional invasion.

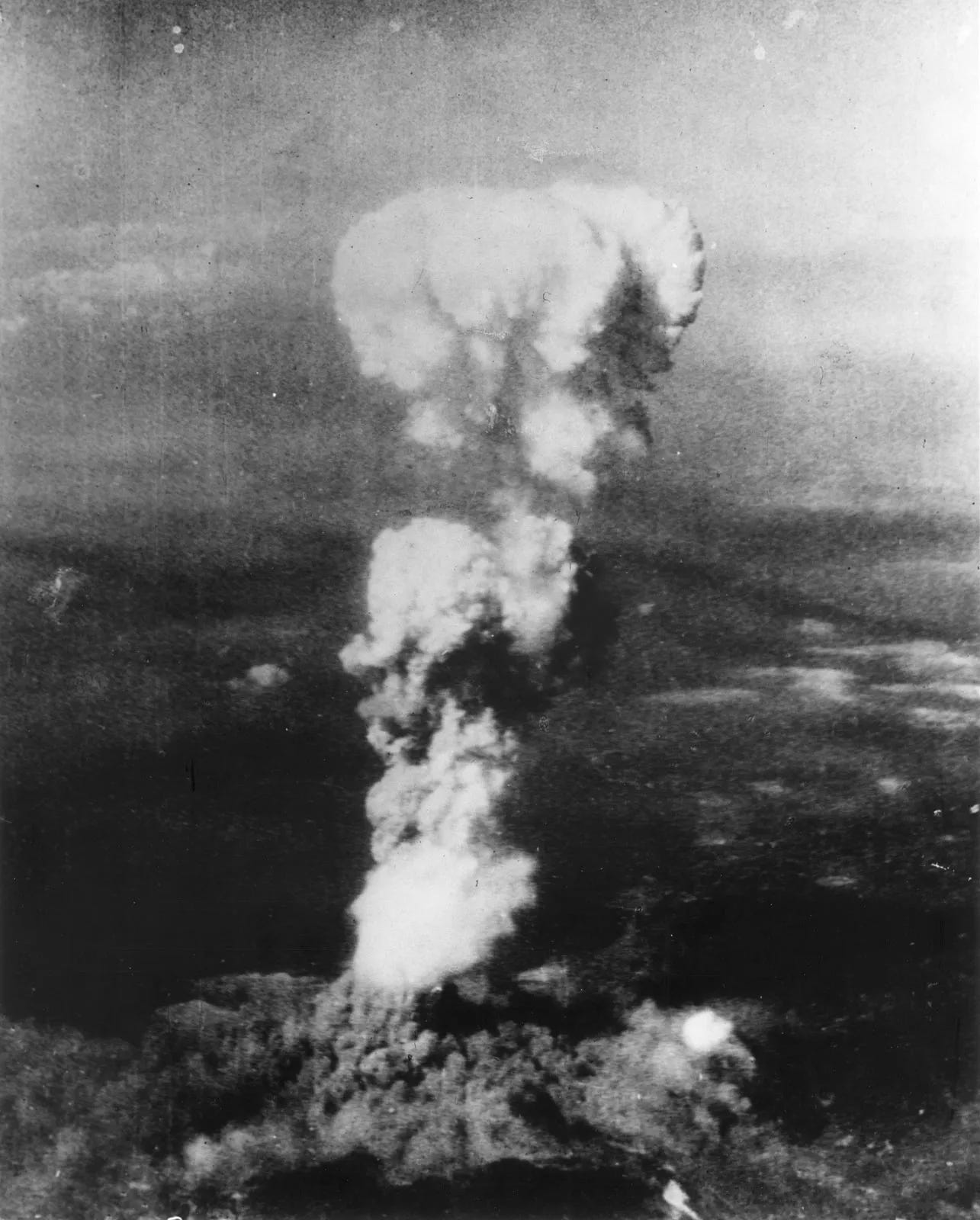

The Atomic Age Begins

The Manhattan Project represented the largest scientific project in history, involving over 130,000 workers. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima (August 6) and Nagasaki (August 9, 1945) killed over 200,000 people and demonstrated unprecedented weapons capability.

These attacks convinced Emperor Hirohito to surrender, achieving their strategic objective of ending the war without the massive casualties conventional invasion would have required. They also announced the beginning of the nuclear age and potential for human self-destruction.

Description: A gigantic mushroom cloud rising above Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945, after a U.S. aircraft dropped an atomic bomb on the city, immediately killing more than 70,000 people

Publisher: Encyclopædia Britannica

Image Source: https://www.britannica.com/event/World-War-II#/media/1/648813/92071

The World Transformed: War's Consequences

The Death of European Imperialism: The war fatally weakened European colonial powers while strengthening independence movements. European countries lacked resources to maintain overseas empires, and within two decades most colonies achieved independence.

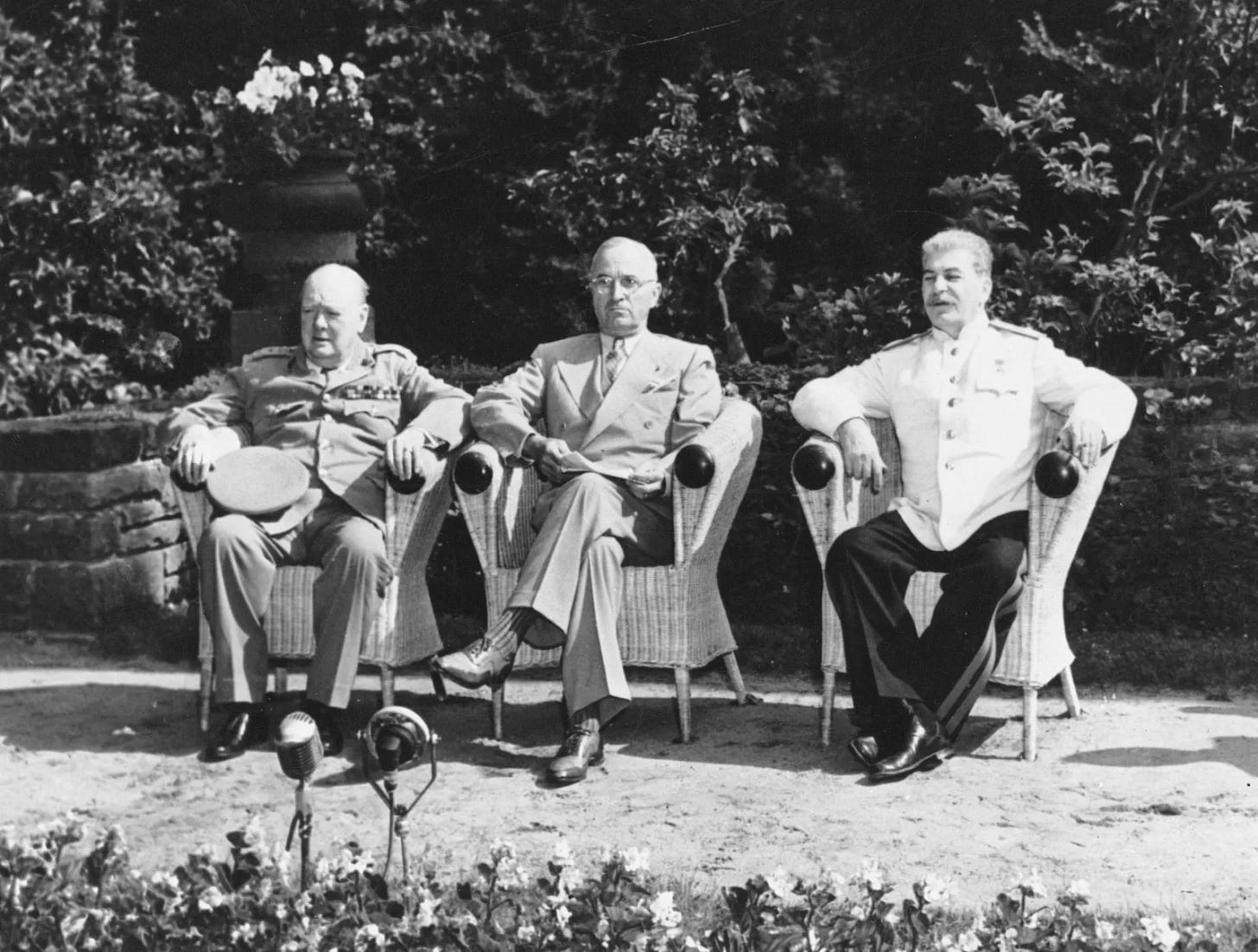

Superpower Emergence: The United States and Soviet Union emerged with capabilities far exceeding other nations. American economic dominance was unprecedented—by 1945, the US produced roughly half the world's manufactured goods.

New International Order: The United Nations provided more effective international institutions than the failed League of Nations, while technological advances in radar, jets, computers, antibiotics, and atomic energy provided foundations for postwar transformation.

Description: British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, U.S. Pres. Harry S. Truman, and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin meeting at Potsdam, Germany, in July 1945 to discuss the postwar order in Europe

Publisher: Encyclopædia Britannica

Image Source: https://www.britannica.com/event/World-War-II#/media/1/648813/92072

Lessons from the Abyss

The war demonstrated civilization's fragility—how quickly civilized societies could descend into barbarism when extremist ideologies gained power. Yet it also showed democratic societies' capacity for extraordinary mobilisation when fundamental values were threatened.

Allied victory required unprecedented cooperation between nations with different systems and cultures, demonstrating possibilities for international collaboration while highlighting isolation's costs. The conflict's moral clarity provides enduring lessons about opposing authoritarianism before it becomes too powerful to defeat peacefully.

Epilogue: The War That Ended Wars?

World War 2 was supposed to end all wars but instead ushered in the Cold War. Yet the conflict's memory continues shaping how we understand international relations and human rights. It established that some values—human dignity, democratic governance, international law—are worth defending at enormous cost.

The war demonstrated both human capacity for remarkable achievement and frightening destruction. The same societies that created the Holocaust also produced the United Nations and modern human rights law. Most importantly, it reminded us that democracy and human rights aren't inevitable—they require active defence by each generation.

In our era of rising authoritarianism, the war's lessons remain urgently relevant. The price of freedom remains, as always, eternal vigilance.

Timeline of World War 2

September 1, 1939: Germany invades Poland; war begins in Europe

June 22, 1941: Germany invades Soviet Union

December 7, 1941: Japan attacks Pearl Harbor; United States enters war

June 4-7, 1942: Battle of Midway; turning point in Pacific

August 1942-February 1943: Battle of Stalingrad; turning point in Europe

June 6, 1944: D-Day; Allied invasion of Normandy

August 6 & 9, 1945: Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

September 2, 1945: Japan surrenders; war ends

Author's Note

World War 2 occupies a unique space in our collective memory—it's simultaneously the most documented conflict in human history and the most mythologised. Everyone knows the broad strokes: Hitler, Pearl Harbor, D-Day, the Holocaust, Hiroshima. Yet beneath these familiar landmarks lies a story so vast and complex that it challenges any attempt at comprehensive telling.

Writing about World War 2 means grappling with an almost impossible scope. This was truly the first global conflict, fought simultaneously across six continents with theatres so different they might as well have been separate wars entirely. The technological gap between the war's beginning and end—from horse-drawn artillery in Poland to atomic weapons over Japan—represents one of the most rapid periods of advancement in human history.

World War 2 serves as both the end of one world and the beginning of another. The war didn't just defeat fascism; it ended the European colonial age, created the nuclear era, established the modern international system, and set the stage for the Cold War. Virtually every major geopolitical reality of the late 20th century emerged directly from this six-year period.

The more you study World War 2, the more you realize that victory often came from the most unlikely moments and unsung heroes. Dunkirk transformed a catastrophic military defeat into a symbol of resilience that kept Britain fighting. Alan Turing and his team at Bletchley Park won battles without firing a shot, using mathematics and early computing to crack codes that historians believe shortened the war by years. These stories remind us that warfare had evolved far beyond traditional battles—success now depended as much on organisational genius, technological innovation, and sheer human ingenuity as on military might.

But perhaps my favourite story from the entire war is Churchill's "We Shall Fight on the Beaches" speech on June 4, 1940. Here was a nation that had just seen its army evacuated from Europe, facing invasion by the most powerful military machine in history, and Churchill's response was essentially to say "bring it on." The speech is masterful—acknowledging military reality while refusing to accept defeat. When he promised Britain would fight "on the beaches, on the landing grounds, in the fields and in the streets," he wasn't just making rhetoric; he was defining what British resistance would look like. It's one of those moments that perfectly captures the power of words to shape reality. Churchill understood that Britain's survival depended as much on maintaining morale and resolve as on military preparation.

The moral dimensions are equally staggering. This was a war where the stakes truly were civilizational—where industrial societies applied their full technological and organisational capabilities to both unprecedented destruction and systematic genocide. The Holocaust represents humanity at its absolute worst, while the Allied response demonstrates our capacity for sacrifice in defence of fundamental values.

Perhaps most importantly, World War 2 offers lessons that remain urgently relevant today. The appeasement of Hitler provides a permanent warning about accommodating authoritarian aggression. The war's outcome validated democratic resilience while demonstrating that freedom isn't self-sustaining—it requires active defence by each generation.

In our current moment of rising authoritarianism and international tension, understanding how quickly civilized societies can descend into barbarism feels more important than ever. The war reminds us that the institutions we take for granted—democracy, human rights, international law—are historical achievements that previous generations paid for with enormous sacrifice.

Disclaimer

This post was created with the assistance of generative AI. Special thanks to the historians whose meticulous research and scholarship made this work possible.

For more information please visit the About section.

https://historytldr.substack.com/about