The Forging of Britain: From Roman Province to Norman Kingdom

How a remote island on the edge of the Roman world became the foundation of one of history's most influential nations through waves of conquest, settlement, and cultural transformation

The Island Empire: How Conquest and Culture Created a Nation

This article explores the tumultuous centuries that forged Britain, from Julius Caesar's first landings in 55 BCE through William the Conqueror's victory at Hastings in 1066, examining how successive waves of Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings, and Normans created a unique civilization that would ultimately reshape the world.

On October 14, 1066, as the sun set over a blood-soaked field near Hastings, King Harold Godwinson lay dead with an arrow through his eye, and with him died Anglo-Saxon England. Duke William of Normandy's victory marked not just another change of dynasty, but the final transformation of a remote island that had spent over a millennium being conquered, settled, abandoned, and conquered again.

The Britain that William claimed bore little resemblance to the Celtic tribal lands that Julius Caesar had first invaded over eleven centuries earlier. Between those two conquests, this island had been transformed from a collection of warring tribes into a Roman province, abandoned to barbarian invasions, settled by Germanic warriors, converted to Christianity, terrorized by Viking raiders, and finally united into powerful kingdoms that could challenge continental powers.

Each wave of invaders—Romans, Angles, Saxons, Vikings, Normans—brought new languages, laws, religions, and technologies that layered upon previous settlements like geological strata. Modern Britain is the accumulated result of these successive transformations, each building upon what came before while fundamentally altering what would come after.

The Celtic Foundation: Britain Before Rome

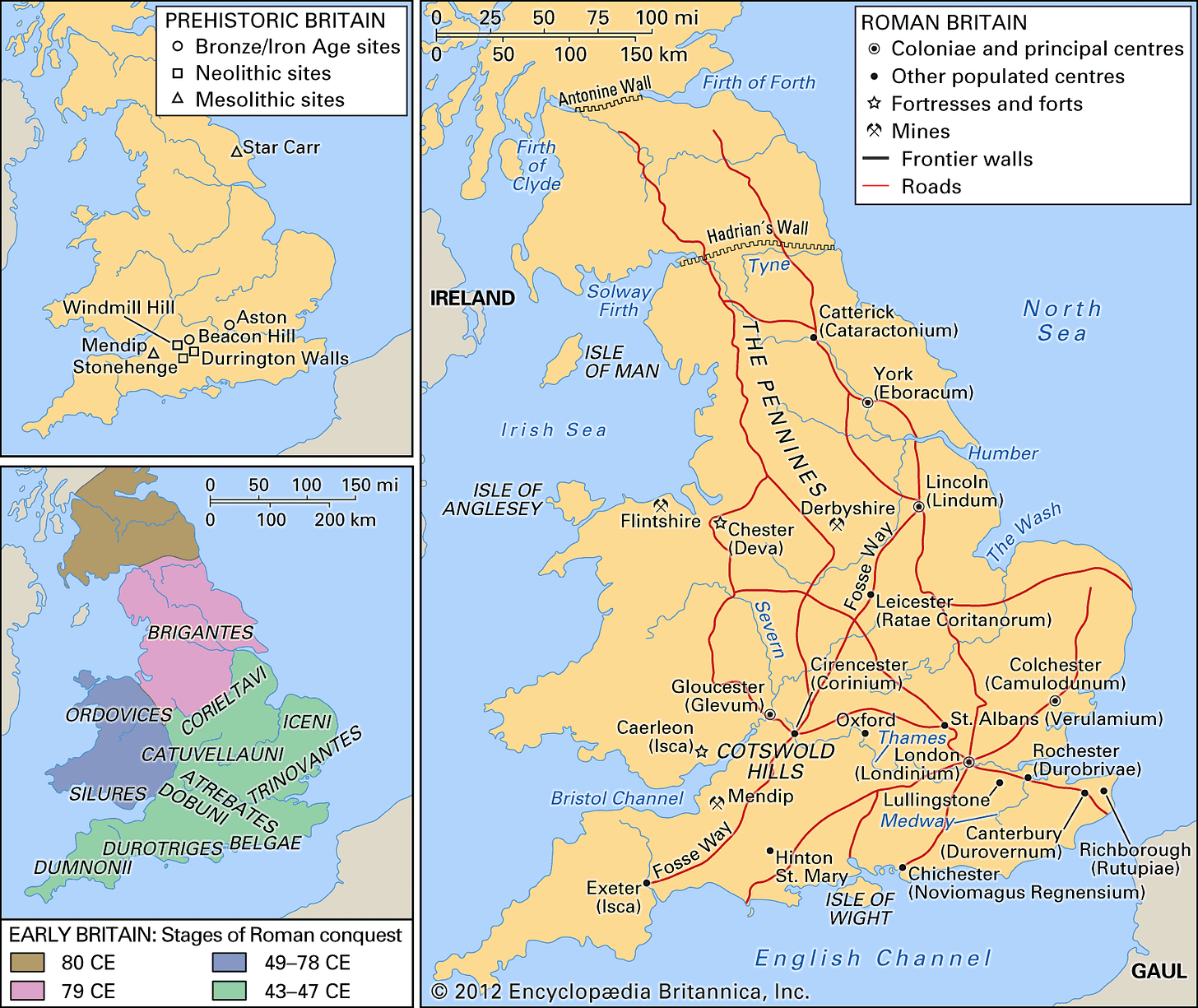

When Julius Caesar first crossed the Channel in 55 BCE, he encountered sophisticated Celtic societies that had been developing for centuries. Pre-Roman Britain was divided among dozens of tribal groups—the Iceni in East Anglia, the Brigantes across northern England (including much of what is now Lancashire and Greater Manchester), the Silures in Wales—each with distinct territories, customs, and often hostile relationships.

These weren't primitive barbarians but organized kingdoms with professional warrior classes, sophisticated metalworking, and extensive trade relationships. The Brigantes, whose territory extended from the Humber to the Scottish borders, were one of the largest and most powerful British tribes, controlling the Pennine hills and river valleys that would later become industrial heartlands.

The Celtic religion, centered on the mysterious Druid priesthood, provided the closest thing to pan-British unity. Celtic Britain was dotted with hillforts—fortified settlements like Maiden Castle that could house thousands and featured complex earthwork defenses. British Celts were master metalworkers, producing weapons and decorative objects that rivaled anything made in the Mediterranean world.

Caesar's Expeditions: The First Contact

Julius Caesar's invasions of 55 and 54 BCE weren't serious conquest attempts but political theater designed to enhance his reputation in Rome. Caesar's first expedition was nearly a disaster, facing determined British resistance and Channel storms. His second expedition penetrated inland and crossed the Thames, but achieved no permanent conquest.

British tactics—using chariots and cavalry to harass Roman infantry—proved initially effective, though individual tribes couldn't maintain unified resistance against professional Roman armies. Perhaps Caesar's most important achievement was gathering intelligence that later emperors would use to plan successful conquest.

The Claudian Conquest: Rome Arrives to Stay

Emperor Claudius's invasion of 43 CE marked the beginning of nearly four centuries of Roman rule. Four legions—over 20,000 professional soldiers—landed in Kent and quickly defeated the southeastern tribes using sophisticated tactics and superior organization.

Within a decade, Roman forces had overrun most of southern and central Britain. The Romans immediately began establishing civilian administration, veteran colonies, and road networks that remained Britain's transportation backbone for over a millennium.

Description: Ancient Britain

Publisher: Encyclopædia Britannica

Image source: https://www.britannica.com/place/Roman-Britain#/media/1/688594/3807

Resistance and Rebellion: The British Fight Back

Roman conquest wasn't accepted passively. The greatest threat came in 60-61 CE when Boudica, queen of the Iceni, led a massive uprising that destroyed three Roman cities and killed over 70,000 Romans. The rebellion erupted when Roman officials brutally mistreated Boudica's family, violating their promises to client rulers.

Boudica's forces completely destroyed Camulodunum (Colchester), Londinium (London), and Verulamium (St. Albans), massacring their populations. The rebellion's ferocity shocked Roman observers, but superior Roman discipline finally defeated the British. Boudica's suicide marked the end of serious resistance in southern Britain.

Hadrian's Wall: The Northern Frontier

The conquest of Scotland proved far more difficult. The Caledonian tribes avoided pitched battles, conducted guerrilla warfare, and proved impossible to subdue permanently. Emperor Hadrian's visit in 122 CE resulted in the decision to build a permanent frontier barrier.

Hadrian's Wall stretched 73 miles from the Tyne to the Solway, marking the northernmost limit of the Roman Empire. The wall wasn't just a barrier but a complex military installation requiring a garrison of 9,000 soldiers. A later attempt to build the Antonine Wall further north was abandoned after twenty years due to constant tribal pressure.

Description: A section of Housesteads Fort, a Roman outpost along Hadrian's Wall in Northumberland, England

Publisher: Encyclopædia Britannica

Image source: https://www.britannica.com/place/Roman-Britain#/media/1/688594/200503

Romanization: Creating Romano-British Civilization

Over nearly four centuries, Roman rule transformed British society, creating a unique Romano-British civilization that blended Celtic traditions with Roman institutions. The Romans introduced true urbanization—cities like Londinium and Eboracum became major centers with forums, basilicas, theaters, and bath houses. In the northwest, Mamucium (Manchester) began as a Roman fort guarding the approach to the Lake District, while Deva (Chester) became a major legionary fortress.

The countryside saw villa estates that combined Mediterranean architecture with British agriculture. Romano-British religion blended Roman and Celtic deities in unique combinations. The Romans built an extensive road network connecting northern settlements—roads that followed routes still used by modern motorways through Lancashire and Greater Manchester.

The Saxon Shore: Defending Against the Sea

By the 3rd century, Saxon raiders from Denmark and northern Germany began attacking Britain's coasts. The Romans built a chain of massive forts along the eastern and southern coasts and employed Germanic foederati—allied barbarian warriors—to fight other barbarians.

The barbarian conspiracy of 367 CE saw coordinated attacks by Picts, Scots, and Saxons that overwhelmed Roman defenses, demonstrating the empire's growing inability to defend Britain effectively.

The End of Roman Rule: Abandonment and Aftermath

The withdrawal of Roman administration around 410 CE was a gradual process of imperial abandonment. Emperor Honorius's letter telling British cities to "look to their own defenses" marked the formal end of Roman rule.

Without imperial support, Romano-British society couldn't maintain the complex systems that sustained urban life. Trade networks collapsed, cities were abandoned, and villa owners fled to hillforts. Archaeological evidence shows rapid urban decline after 410 CE.

The Anglo-Saxon Settlement: New Peoples, New Culture

The arrival of Anglo-Saxon settlers from northern Germany and Denmark represented not just military conquest but demographic replacement that fundamentally altered Britain's ethnic and cultural composition. Saxon settlement involved significant population replacement in eastern and central England, though the northwest—including the former Brigantian territories around Manchester—remained more contested.

The most dramatic evidence is linguistic—Celtic languages disappeared entirely from most of England, replaced by Anglo-Saxon dialects that evolved into Old English. Only in Wales, Cornwall, and the northwest did Celtic languages survive longer, with Cumbric (a Brittonic language related to Welsh) persisting in parts of Lancashire and Cumbria until medieval times.

By the 7th century, Anglo-Saxon England had organized into seven major kingdoms: Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, and Sussex. The northwest found itself on the contested border between Mercia and Northumbria, with control shifting repeatedly between these powerful kingdoms.

The Conversion to Christianity: Cultural Revolution

The conversion of Anglo-Saxon England between the 6th and 8th centuries represented a cultural transformation as significant as the original Saxon settlement. Pope Gregory's dispatch of Augustine to Kent in 597 CE began systematic Christianization, working through royal conversion followed by popular evangelization.

Irish missionaries simultaneously brought different Christian traditions from the west. Anglo-Saxon monasteries like Jarrow and Lindisfarne became centers of learning that preserved classical knowledge while developing new scholarship and art, producing figures like Bede and masterpieces like the Lindisfarne Gospels.

Anglo-Saxon Christianity created a unique synthesis of Germanic warrior culture, Roman learning, and Celtic spirituality that shaped English civilization.

The Viking Age: Terror from the North

The attack on Lindisfarne monastery in 793 CE shocked the Christian world and announced the beginning of the Viking Age. These early raids targeted monasteries—repositories of wealth and symbols of Christian civilization—creating fear that lasted generations.

The Great Heathen Army's arrival in 865 CE marked a new phase—systematic conquest rather than raiding. Led by legendary figures like Ivar the Boneless, Vikings conquered East Anglia, Northumbria, and much of Mercia. The northwest, including the area around Manchester, experienced intense Viking settlement, with Scandinavian place names like Urmston (Ormestūn) and Flixton still evident today.

King Alfred of Wessex led Anglo-Saxon resistance, his victory at Edington (878 CE) establishing the Danelaw—formal Viking settlement in eastern England. The northwest became particularly Scandinavianized, with archaeological evidence suggesting dense Viking settlement throughout what would become Lancashire and Greater Manchester.

The Unification of England: From Kingdoms to Nation

Alfred's successors systematically reconquered the Danelaw. Edward the Elder and his sister Æthelflæd combined military pressure with fortress construction, while Æthelstan completed unification by conquering Viking York and forcing Scottish and Welsh submission.

The unified English kingdom developed sophisticated administrative systems—shire organization, royal reeves, standardized law codes—that provided effective governance over large territories. The alliance between church and crown created new concepts of sacred kingship that elevated royal authority above traditional Germanic leadership.

The Second Viking Age: Renewed Assault

The late 10th century brought renewed Viking attacks that tested the unified kingdom. King Æthelred II's policy of paying Danegeld only encouraged further attacks, while his massacre of Danish settlers (1002 CE) provoked massive retaliation.

Sweyn Forkbeard conquered England briefly, but his son Cnut established lasting Danish rule (1016-1035), creating an empire including England, Denmark, and Norway. Edward the Confessor's restoration (1042-1066) brought back the English royal line, but increasing Norman influence set the stage for the final conquest.

The Norman Conquest: The Final Transformation

Edward the Confessor's death created a succession crisis with multiple claimants. Harold Godwinson's victory over Norwegian Harald Hardrada at Stamford Bridge eliminated one threat, but William's landing forced an exhausting march south to Hastings.

The Battle of Hastings demonstrated Norman combined-arms tactics against Anglo-Saxon infantry. William's systematic conquest included the devastating Harrying of the North (1069-1070) and the comprehensive Domesday Survey (1086) that documented the transfer of virtually all major landholdings from Anglo-Saxon to Norman control.

Description: The death of Harold II at the Battle of Hastings, detail from the Bayeux Tapestry; in the Musée de la Tapisserie, Bayeux, France. Harold, on the left, has been struck in the eye with an arrow

Publisher: Encyclopædia Britannica

Image source: https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-I-king-of-England#/media/1/643991/252318

The Norman Impact: Remaking England

The Norman Conquest introduced continental feudalism, massive stone architecture, and sophisticated administration that combined Anglo-Saxon institutional traditions with Norman practices. French language and culture transformed the English elite while gradually creating new syntheses of Norman and Anglo-Saxon traditions.

The development of Middle English from the collision of Old English and Norman French created a new language that was both European and distinctively English.

Legacy of Conquest: The Foundation of Medieval England

The waves of conquest between Caesar and William created the foundation for everything that followed in English history. Despite constant upheaval, institutional traditions showed remarkable continuity, with each conquest creating cultural synthesis rather than replacement.

The successive conquests progressively integrated Britain into European networks while creating powerful mythologies about English resilience and adaptation. By 1066, England was no longer an isolated island but a central European player.

Epilogue: The Island Transformed

The millennium between Caesar's landing and William's conquest transformed Britain from tribal territories into a unified kingdom capable of projecting European power. This occurred through constant upheaval, yet the underlying continuity—shaped by geography and the accumulated wisdom of governing this particular island—influenced all rulers regardless of origin.

By 1066, Britain had become uniquely European yet distinctively English. The Norman Conquest represented the culmination of this process, creating a synthesis that would make England one of medieval Europe's most dynamic societies.

The experience of repeated conquest and adaptation created a political culture uniquely capable of absorbing foreign influences while maintaining institutional continuity. This adaptability would prove crucial when England became a conquering power, able to rule diverse populations precisely because it had learned through being ruled by diverse conquerors.

The island that had once been the Roman world's edge was ready to become the center of its own empire.

Timeline of Early British History

55-54 BCE: Julius Caesar's expeditions to Britain

43 CE: Claudius begins Roman conquest

60-61 CE: Boudica's rebellion

122 CE: Hadrian's Wall constructed

410 CE: End of Roman rule

597 CE: Augustine arrives in Kent

793 CE: Vikings raid Lindisfarne

878 CE: Alfred defeats Vikings at Edington

1066: Norman Conquest; Battle of Hastings

Author's Note

Writing about early British history presents unique challenges since we're covering over a millennium through limited and often biased sources. Most of our "British" history was written by outsiders—Caesar glorifying his achievements, Roman historians describing resistance through imperial eyes, Norman chroniclers justifying conquest.

As someone from Manchester, I find this topic particularly fascinating because I'm literally walking through landscapes shaped by every wave of conquest described in this article. The Brigantian territory I live in was Romanized, then became contested borderland between Saxon kingdoms, was heavily settled by Vikings (evident in local place names), and was finally reorganized under Norman rule.

Perhaps most importantly, studying this period reminds us how contingent historical development really is. There was nothing inevitable about English unification or Norman conquest—different decisions or timing could have produced completely different outcomes. The "English" didn't exist until the Anglo-Saxon period, and even then regional identities often mattered more than national unity. We're telling the story of the island itself—how successive peoples interacted with Britain's geography and each other to create something new, building up layers of civilization like writing over the top of an already existing document.

Disclaimer

This post was created with the assistance of generative AI. Special thanks to the historians whose meticulous research and scholarship made this work possible.

For more information please visit the About section.

https://historytldr.substack.com/about